Fast, deadly & loveable: The real Sylvester Clarke

In Sylvester Clarke, Surrey, between 1979 and 1988 had the most feared bowler in cricket. Not just county cricket, any cricket. Just ask Geoffrey Boycott. Alan Butcher knew just what it was like to face him and was therefore mighty relieved to have him as a teammate.

The Editor’s Choice in the summer 2018 issue of The Nightwatchman, Butcher’s first-hand account forms part of our series marking 50 years of overseas players in county cricket.

A cricket ground. Somewhere in Nottinghamshire. The early 1980s. Notts Second XI are taking on Surrey Second XI. Both teams have their usual mix of embittered out-of-favour pros, young hopefuls, desperate-to-impress triallists and decent club players.

But Surrey’s team is slightly different. For reasons lost in the mists of time – possibly as a part of injury rehab or because regulations stipulate that only one of their overseas players can play in the first team – the second XI have the most feared fast bowler in county cricket on their team sheet.

Anyone who played second-XI cricket at that time would have come across many overseas pacemen relegated to the stiffs as a result of the domestic regulation. It was great preparation for first-team cricket, even if some of the club pitches were themselves underprepared.

Surrey in 1982: Back row: Monte Lynch, Jack Richards, David Thomas, David Smith, Sylvester Clarke, Graham Monkhouse, Paul Taylor; Front row: Graham Roope, Alan Butcher, Roger Knight, Robin Jackman, Geoff Howarth

But the identity of the man in question makes this scenario unlikely. For this is your main man, your go-to man, your star man. You do not inflict the indignity of banishment to a far-flung outpost on your star man without good reason.

But that doesn’t mean that your star man is immune from having indignity inflicted upon him in his own dressing-room. And so it happened that on the final day of that second-XI fixture a young Surrey hopeful and renowned practical joker, Martin Bamber, arrived early in the away dressing-room and affixed a rubber clothes hook to the wall where the star man was changing.

In comes the star man a few minutes later, deep in conversation, and hangs his jacket on the peg. Turning to take off his tie, he hears the jacket hit the floor. He picks it up, replaces it on the peg and returns to the conversation, only to hear the jacket hit the deck once more. Eventually twigging that he’s been done, the joke is taken in good part, the culprit identified.

Surrey bat last that day, which gives the star man – no mean joker himself – a chance to plot revenge. At the end of the day he changes quietly, watching Bamber’s progress as he gets dressed after his shower. Underpants on, socks on, shirt on, tie neatly knotted. Then the trousers. Trousers? There are no trousers. Where are the trousers? And Bamber begins a frantic search for the missing item of clothing while the star man, shoulders heaving with laughter, is enjoying sweet revenge, the trousers fluttering in the breeze at the top of a flagpole on the opposite side of the ground.

The star man is Sylvester Clarke, Surrey’s feared and ferociously fast overseas bowler of great legend from 1979 to 1988. I tell this story of dressing-room japes and puerile pranks not so much to amuse as to try to humanise a teammate who has so often been unfairly dehumanised.

Now I do not wish to give the impression that Clarke – “Silvers” – was not a mean and nasty proposition for batsmen when he had a cricket ball in hand. Some batsmen will tell you he was the meanest and nastiest of all, and for some reason he hated it when batsmen, usually tail-enders but not always, backed away from him. He would openly admit that when it happened it upset him so much that he would try to “follow” the culprit. Encouragement to bowl straight and full and blast the stumps out was met with: “Nah, I gonna hit he.”

It was a blind spot. Backing away offended his sense of how the game should be played and contributed hugely, and unsurprisingly, to the view that he was brutish and unfeeling. Interestingly, Clarkey himself wasn’t the bravest with bat in hand, perhaps an example of the “you hate in others what you least like in yourself” strand of psychology. At any rate, we had the devil’s own job getting him to bowl Malcolm Marshall a bouncer whereas Maco had no such compunction and, much to our amusement, regularly dumped Silvers on his arse. On one occasion at Old Trafford, when Michael Holding was working up a head of steam, Clarke swung wildly at three balls in succession, nicking them all but with so much bat speed that they burst through the hands of the slip cordon. He got to the other end, a wicket fell and he hurried to meet the incoming batsman. “Perce!” he screamed at Pat Pocock with wild, staring eyes. “Perce, you can have a piece of he… he comin’ tru like a train!”

But would an unfeeling and brutish man inspire the kind of genuine affection that his teammates and their families had, and still have, for him? Would the club’s supporters have taken him so much to their hearts? Would so many of his fellow Bajans have turned up to fill the sizeable St Patrick’s church not just with people but with respect and love and grief for the untimely loss of a 44-year-old man who had stayed true to his roots, sticking with his beloved Crusaders CC in the Barbados Cricket League rather than moving up to a more fashionable Barbados Cricket Association club? The answer to all of those questions is an emphatic “no”.

***

The arrival of Sylvester Theophilus Clarke to SE11 in April 1979 was the cherry on a cake that had been baking since the end of the previous season. Micky Stewart had stepped into the role of cricket manager, the moribund pitches of the ’70s had been relaid in an effort to provide pace and bounce, and some good signings had been made. Bizarrely, a three-week pre-season party in Hong Kong, Singapore and Bangkok – with a bit of training and fairly low-quality cricket preparation thrown in – turned out to be a fantastic way for a hitherto fractured squad to gel. The trip, organised before the appointment of the new cricket manager, was anathema to Stewart, offending his notion of professionalism. But he threw himself into the fun, the drinking games and more than once became the victim of them. We didn’t realise it but the squad that stepped off the plane on our return was vastly superior to the one that left Heathrow three weeks earlier.

And in walked Silvers.

Stewart remembers meeting him for the first time when he picked him up from the airport. He recalls “a tiny fellow” helping him with his bags. “What’s this Sylvester?” joked Micky. “Have you brought a servant?” “Nah, manager, this is Mr Malcolm Marshall.”

So two overseas legends arrived in London on the same day, one bound for Southampton and international greatness, the other for Kennington and legendary status of a sort, and a place in the hearts of all those who played with him.

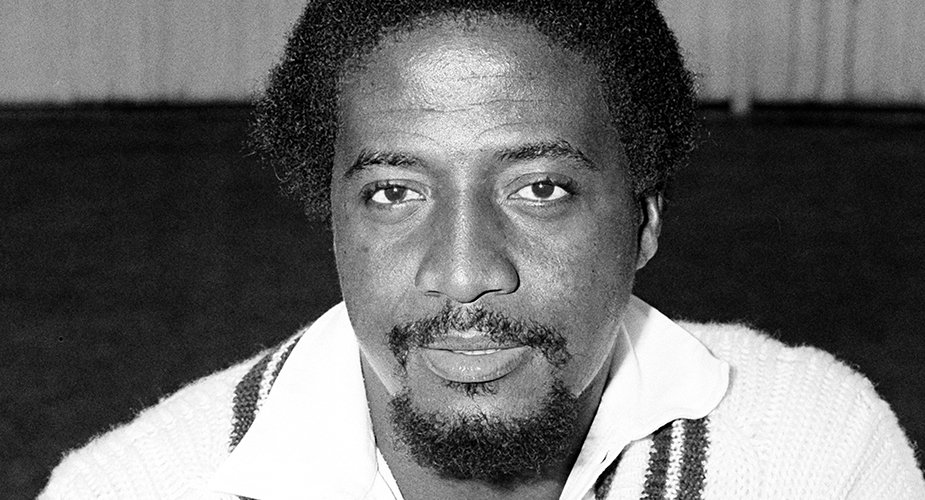

‘Silvers’ for Surrey in 1987

I don’t want it to sound like Clarkey rode into town like the lone ranger and single-handedly rescued the cowed and pathetic villagers from the yoke of a band of desperadoes. That would be disrespectful to those such as Robin Jackman, Pat Pocock, Intikhab Alam and Graham Roope, who had all toiled manfully for Surrey – not without success – throughout the doldrums of the mid-70s. But it is fair to say that his arrival drew our bowling talents together to form a pretty formidable attack, with Clarke the undisputed spearhead. He punched holes in the opposition line which the rest could then charge through. Witness 93 first-class wickets for Jackman and 70 for Pocock in 1979, Clarke’s first season at Surrey.

Silvers did what great overseas players do, which is provide wickets or runs. Or both. But they offer more than the bald statistics. The best bring with them confidence that can spread through the whole team. It may well be the type of confidence that comes from knowing that your best mate is the biggest and strongest boy in the school, but it’s real, it feels good and, along with our newly acquired mateship, it enabled everyone to blossom and cricket to feel fun again.

Even the batsmen caught the vibe. In 1979 the top three all scored 1,000 runs for the first time in living memory, and Nos.4 and 5 came within an underarm lob of that figure. We were not perfect but a rise from 16th to third in the County Championship, plus a one-day cup final, was a huge improvement. And it should not be passed over that Clarke played only half of our Championship programme because of injury. In common with every other county, we were streets behind Essex in the Championship – and some way behind them in the B&H final too. But within the dressing-room we felt like a decent team again.

***

The seeds of this revival had been sown at the end of the previous summer. Word of Sylvester’s exploits in league cricket up north had filtered down south and so it was that I was called upon to put my pads on, shortly after dawn it seemed to me, and do battle on an unprepared, end-of-season, end-of-square wicket against a rather large gentleman from Barbados who was a prospective overseas signing. You may glean that I wasn’t that keen.

However, he appeared an amiable chap and so I sauntered out to the middle with wicket-keeper Jack Richards and the coach. Clarke measured out a reassuringly short run, swung his arms once or twice, checked that I was ready and set off on an ambling, none-too-threatening approach. “This’ll be a loosener,” I thought. He reached the crease, chest-on, his arms did a kind of double-whirl which propelled the ball in at middle and leg stump at great pace just short of a length, and I opened up slightly to access the ball, which pitched and veered sharply away from me, and steepled over my left shoulder to be taken by Richards on the rise.

It was at this point that I realised we had an audience. For as I looked around to see where the missile had gone, I saw my teammates hooting and hollering and offering advice. “Get forward Butch!” “Hook him!” Thanks guys. Very helpful.

Butcher was the victim of Clarke’s Surrey trial

Clarke was now back at the top of his run, preparing to run in to a batsman who was suddenly wide awake. Same ambling run, same double-whirl, the ball once again steepling over my left shoulder into the gloves of the keeper. “I reckon that’s me done, coach,” I said. “He’ll do for me!” Clarke was duly signed, and from 1979 to 1988 he took 591 wickets at 18.99. Not a bad morning’s work on my part!

So what made him special? Well, great pace obviously, with a front-on action that angled, swung and seamed the ball back into the right-handed batsman, following him alarmingly with a rising bouncer or zoning in on his toes with a wicked yorker. He was immensely strong, which contributed greatly to both pace and bounce, and he had the ability to bowl a prodigious number of overs for a strike bowler. Recently I was watching a live stream from Old Trafford of the Lancashire v Surrey Championship match and was perplexed by Surrey’s tactics – at one stage the home team were 128 for 5 but there seemed no real effort to bowl them out. The three main seamers had got wickets but each had bowled only 15 of the 83 overs by the time their opponents had recovered to post a total of 400-plus. Contrast that with a match between the same teams at The Oval in 1979, when Surrey bowled Lancashire out for 190 in 83 overs – 63.4 of which were shared by Clarke and Jackman. Make of that what you will, but it’s no secret that neither of the pair were notorious for their fitness regimes. In fact I think they were dyslexic, for they both spelt gym “b-a-r”. But when they saw the chance to run through a batting side, they did not hold back.

To be fair to Clarke, he didn’t rely on these attributes; he sought to improve himself as a bowler and learnt to swing the ball away. Perversely, this didn’t actually make him a more effective bowler because a right-handed batsman’s natural assumption was that Clarke’s action would angle the ball in; the slightest movement away meant that he missed the ball by a long way. I suspect, though, that he enjoyed making a batsman look foolish almost as much as he did getting him out. At least it seemed that way to me when, facing him in the nets, he’d bowl that ball in at middle and leg, the same one he bowled to me at his trial, the one I never worked out how to play. Hips opening slightly to access the line then jerking involuntarily back to counter the rapid movement across me and Clarke, standing in the middle of the pitch, shoulders heaving, laughing at me. “Butch, I got you dancing, Butch!”

His career statistics bear comparison with any of his contemporaries. It is a matter of record that Sir Garfield Sobers thought Clarke had the attributes to be the best of all West Indies quicks. Sir Viv Richards has stated that Clarke was the bowler that made him feel most uncomfortable. Alec Stewart is unequivocal in his assertion that he was the fastest he ever saw and chuckles at the memory of his first encounter with the big man at the indoor nets at the Bank of England sports ground at Roehampton: “I was 16, in my school cap and Clarkey would shout ‘bouncer’ just before letting it go to give me time to get underneath it!”

He was revered and is still spoken of (though in hushed tones) in South Africa, where he took part in a rebel tour and went on to represent three provincial teams with great distinction. But he did not, by a long stretch, have the success on the international stage that his ability and statistics warranted.

On 1983’s rebel tour to South Africa

It is simple to point to the abundance of fast-bowling riches that West Indies were blessed with at the time, but that is not the full story. It is wholly in keeping with Silvers’ character that he should sign up for a rebel tour – he could see his international opportunities were limited, sure, but he also had a rebellious streak, a problem accepting authority. A common refrain was: “Dis is bare rubbish. It don’t mek no sense.” What today are called the one per-centers – the little things that teams buy into to give them an edge – he could in most cases see no merit in. For him it was: get on the pitch, bowl like the wind, dismiss the opposition and then enjoy. And there were others of us who shared his philosophy.

Let us go back to Micky Stewart’s first meeting with Clarke and that “little fellow” Malcolm Marshall. They had not long returned from a West Indies tour of India where Clarke, four years older at 24 but still a rookie, was very definitely first-choice. Outside international cricket, their bowling averages are remarkably similar. It’s when you look at output that the difference is stark. Marshall’s career was seven to eight years longer, he played 170 more first-class matches and as a result he took nearly 700 more wickets. Yes he started younger, was highly skilled and a shrewd tactician but Clarke could match that. What he couldn’t match was Marshall’s personal discipline, his dedication to fitness and preparation. Clarke would have been a maverick in what was a great and very disciplined West Indies bowling unit, notwithstanding New Zealand 1979/80. Add in the huge and nearly catastrophic lapse of judgment that led him to throw a stone used to mark the boundary into the crowd in Multan because he was being pelted with pebbles, and you have someone that Clive Lloyd perhaps didn’t wholly trust, a personality he didn’t really need.

It was a personality that suited us fine. He was fun, amusing, engaging. He could be generous and was kind to players’ partners and children. I’ll never forget the look of wonder on his face at his first experience of snow settling on his sweater one evening in Cambridge during his debut season. I won’t forget the hurt in his eyes after enduring monkey calls and being pelted with bananas while fielding in a Sunday League match at Hull later that year. Nor how he tore into the Yorkshire batting line-up with a visceral passion ever after, in particular during the Gillette Cup semi-final in 1980, when the humiliating experience was still fresh.

This was a match that was played in the most highly charged, almost malevolent atmosphere of any I took part in. It was a dark, stormy day, early rain had delayed the start and bad light had lingered. Yorkshire always brought a big crowd and they were getting restless. There were arguments with the umpires after their inspections, and the teams were being blamed for not wanting to play. Eventually around two o’clock we got underway. It was still very dark, with lightning and rumbles of thunder. Whoever won the toss that day was going to bowl first and there was menace in the air as Geoff Boycott and Bill Athey began the Yorkshire innings. Clarke unleashed everything at them. He was too quick for Boycott, he split Athey’s helmet in two, and he bowled one bouncer that I swear when I watched it back on TV later that night looked as if it would bounce clean through the screen. It was terrifying. But my goodness it was electrifying.

He was the same in another 60-over semi-final six years later against Lancashire when he tore into Clive Lloyd, perhaps to demonstrate what West Indies had been missing but also because Lloyd had the temerity to stroll out in a white floppy hat with the score on 8 for 2 and Clarke bowling at the speed of light. He gave Lloyd a real working-over but the batsman stood firm. My clearest memory is being summoned to third slip. With Clarke charging in and Lloyd displaying incredible bat speed, I was praying that he didn’t nick off to me, for I had no chance of catching it – even standing some 20 yards back.

Thinking about these things now brings a warm feeling, a smile, a chuckle. Even the day at Grace Road when an appeal for a catch at the wicket against my brother Ian was turned down. I was at short leg so had no view but there was a noise and Clarke was convinced. “You hit dat, Butch?” he asked. A shake of the head was the reply. Clarke also shook his head. “You hit dat, Butch” he said again, but this time it was a statement. Both Butchers knew what was coming and I was in the uncomfortable situation of being witness, from two yards away, to my brother repelling a ferocious bowling onslaught. He showed a lot of guts and I was proud that he saw it through. To this day I still ask him: “You hit dat, Butch?” He is yet to tell me the truth.

***

I was there right at the start of Sylvester’s Surrey career and there seemed to be a thread running through our lives. It continued post-retirement when I holidayed in Barbados with my family, only to find it coincided with Clarke’s marriage to Peggy, his long-term girlfriend and mother to Shakeem, an up-and-coming pace bowler, and Sasha, a DJ at last report. Sadly, in December 1999 the thread ran out when Sylvester died a day before I arrived in Barbados as part of the management for a Surrey under 19 tour. I delivered a tribute on behalf of the club, his teammates and myself as a friend, and helped lay him to rest in St Patrick’s cemetery.

It’s a beautiful sunny day as I write this and my mind goes back to an evening on a similar day when we were playing Somerset at Weston Super Mare. A challenge was laid down between our champion ST Clarke and some local upstart by the name of IT Botham. The choice of weapons was white wine and whiskey chasers and, to cut a long story short, Botham won hands down. A few hours later Clarke had to bat with Pat Pocock to try to get us out of a deep hole. In the first few minutes Pocock drilled a straight drive towards Clarke who, unable to move, sustained a blow on the forearm, necessitating his retirement to a safe place stretched out under the physio’s bench.

Unprofessional, you might be thinking. Immature, childish. And yes, it’s true. But if I have the choice between thinking about Sylvester Clarke stretched out in St Patrick’s cemetery or Sylvester Clarke stretched out under a physio’s bench at Weston Super Mare, knowing that in a couple of hours he’ll get up, shake his head, swing his arms a couple of times and then amble in to bowl at the speed of light, well then I’m sorry; that’s where I’m going to go, every time.

This article first appeared in issue 1 of The Nightwatchman, the Wisden Cricket Quarterly

Buy the 2018 Collection (issues 21-24) now and save £5 when you use coupon code WCM8